He was found by the Bureau of Statistics to be

One against whom there was no official complaint,

And all the reports on his conduct agree

That, in the modern sense of an old-fashioned word, he was a saint,

For in everything he did he served the Greater Community…The Press are convinced that he bought a paper every day

And that his reactions to advertisements were normal in every way.

Policies taken out in his name prove that he was fully insured,

And his Health-card shows he was once in a hospital but left it cured.

Both Producers Research and High-Grade Living declare

He was fully sensible to the advantages of the Installment Plan

And had everything necessary to the Modern Man,

A phonograph, a radio, a car and a frigidaire…—W. H. Auden, “The Unknown Citizen,” 1940

At the center of “The Unknown Citizen,” one of the first poems written by W. H. Auden after his migration to the United States in 1939, is an individual identified only through bureaucratic enumeration. This anonymous citizen is known in purely external and calculable terms, a product of official government agencies—a fictional “Bureau of Statistics”—and an object of corporate, social scientific, marketing, eugenic, and polling scrutiny. The closing lines of the poem point simultaneously to the hubris and limits of statistical knowledge about citizens: “Was he free? Was he happy? The question is absurd: Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard.”[1]

Written in the form of a state epitaph for an “unknown” but all too knowable citizen, Auden’s poem is an apt starting point for thinking about the implications of making the unseen seen. I want here to consider the visibility permitted by quantification, a form of social description with far-reaching, if unpredictable, consequences. The history of statistical representations concerns precisely the ways previously unenumerated entities are imagined, visualized, and assimilated. In my own work, “typical citizens,” “majority opinion,” “normal sexuality,” and “the American public” itself all became newly palpable concepts in the mid-twentieth century, in part because of the persuasive force of mass surveys and aggregate statistics.

Recently, sociologists Wendy Espeland and Mitchell Stevens have called for treating numbers as speech acts: numbers “do” things as well as “say” things and bring about change as an effect of “saying something.” [2] As they point out, public understandings of crime and health, poverty and gross domestic product, intelligence and educational quality—just to name a few foundational social concepts—are not just undergirded by but absolutely constituted by quantitative measurement. Alain Desrosieres puts it this way: “The aim of statistical work is to make a priori separate things hold together, thus lending reality and consistency to larger, more complex objects.” [3] In this rather potent conjuring act, the invisible and unstable become permanent and actual.

Indeed, recent history suggests that almost nothing in the social world that is presumed to “count” can resist visibility in the form of quantitative measurement. No matter how complex, elusive, and challenging the object, there are those dedicated to coaxing it into coherence and analysis, and in that sense making it “real.” Numbers, of course, can be both reductive and productive. As Alice O’Connor has shown, the capture of poverty by economistic measures in the United States shut down certain ways of thinking about the category (as structural rather than individual, for instance), constraining possible policy options for curbing it. [4] On the other hand, Ian Hacking, who has argued that social classifications play a role in “making up people” (“the pervert” or the “split personality”), slyly suggests that counting and categorizing—in the form of tables of occupations—were unwittingly responsible for class consciousness and perhaps Marxism too. [5]

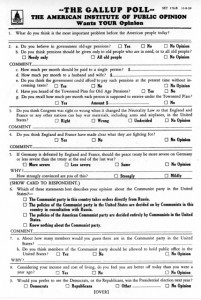

This 1939 questionnaire from the American Institute of Public Opinion suggests the range of questions put to Americans about public and personal affairs by doorstep pollsters. (Gallup Poll questionnaire, 1939)

Quantitative description is often a technology of apprehension—of objects, its rhetoric insists, that already exist but have been inadequately perceived. But the same processes have the power to render other things invisible. Not the least of these is the technical process by which a certain version of reality is created, thereby complicating efforts to undo it. Successful classification naturalizes its categories, allowing them to retreat from sight. [6] It is precisely this paradox that gives statistical facts their potency: the more that survey technologies, for example, are regarded as unremarkable and matter-of-fact, the more difficult it is to discern their capacity to define entire domains of social life. And this is not even to say anything about “agnotology,” Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger’s neologism for the “study of culturally constructed ignorance” (a close cousin to Steven Colbert’s “truthiness”). Statistics have played a starring role in the “manufactured uncertainty” central to the tobacco industry and climate-change denials, and in “how and why various forms of knowing do not come to be, or have disappeared, or have become invisible.” [7]

The colonization of the social by numbers has a long history, beginning with early tax rolls and censuses. But it took new forms in the twentieth century, when—despite considerable suspicion and controversy—ordinary people’s habits, opinions, and behaviors were all submitted to quantitative measures. This was a distinctly modern project of monitoring the inner life of national populations, their private beliefs and desires. It required new tools, new kinds of coordination, and new ways of thinking, and became a key ambition of policy-makers, corporations, and social scientists alike. Intricate methods of collecting and displaying aggregate information have become ever more intertwined with the public sphere. As such, it is worth asking: How have citizens become known through numbers, and with what effects on subjectivity and social life? Or in slightly different terms, what are the links between new means of perceiving the social and new modes of experiencing it?

One conclusion is clear from my investigation of the rise of new forms of survey knowledge in the last century. Americans, I argue, began to imagine themselves as “statistical citizens,” members of a modern public that saw itself reflected in aggregate data collected from anonymous others. These data lent real substance to the idea of the “mass,” bestowed new cultural weight on the imagined mainstream, and worked to highlight and regulate differences.

Individual responses to this process varied, but they all reveal the thickening bonds between statistical representation and social reality. Many citizens vehemently protested the polls and statistics that purported to describe them in guises as different as the Gallup Poll and the Kinsey Reports, hoping to substitute their own numbers for the experts’. Others worried about the sway of aggregates, including their power to create new norms and behaviors—a version of Espeland and Stevens’ speech acts. Still others, however, happily volunteered and disclosed theretofore private information, in part to make their mark on, and become visible in, the new surveys. Most interesting were those who located themselves in newly accessible statistics, willfully inhabiting the categories of surveyors and communing with strangers known only through tables and charts. [8] In this sense, numbers that persuasively stood in for social reality had significant repercussions. They not only helped consolidate an official public but also shaped individual subjects.

A second conclusion is that quantitative measurement has become central to late-twentieth-century and early-twenty-first-century understandings of privacy. In part because citizens have been made so visible to the “Bureaus of Statistics” (to return to Auden), whether those of the state, private employers, marketers, or polling agencies, some individuals have sought to resist legibility—to evade the elaborate bureaucratic and corporate strategies designed to know them. This kind of privacy is new. And it has had some successes, small interventions (perhaps only temporary) that have managed to halt the flow of information. Most have proliferated since the 1970s: unlisted phone numbers and addresses; “dark routes” to escape CCTV cameras; Census protests; opt-outs from Google street maps. Each of these is a response to visibility and a technique for leaving fewer marks on the official records that have become so ubiquitous in recent decades.

What is clear is that enumeration is once again creating visions of the social—and visions of the self—if in distinctly novel, and perhaps not yet obvious ways. One recent commentator, for instance, writes that “our physical bodies are being shadowed by an increasingly comprehensive ‘data body,’” a body of data, moreover, that “does not just follow but precedes the individual being measured and classified.” [9] Grégoire Chamayou has speculated that such “techniques of traceability” have generated novel aspects of individuality through the concept of personal data, which he provocatively calls a “numerical avatar” and a “schematic and centralized double of ourselves.” [10] What is still clearer is that an aspired-for invisibility is rooted, at least in part, in the conviction that society’s accountants know too much about us, that there can no longer be an “unknown citizen.” In this way, quantitative measurement has been at once a tool for elucidating social life and a trigger for rethinking social values. If privacy of this new sort has become a key aspect of modern citizens’ sense of self, it is in part thanks to those entities that have sought so relentlessly to “sense the unseen.”

[1] W. H. Auden, “The Unknown Citizen,” Another Time (New York: Random House, 1940).

[2] Wendy Nelson Espeland and Mitchell L. Stevens, “A Sociology of Quantification,” European Journal of Sociology 49: 3 (2008), 401-36.

[3] Alain Desrosieres, The Politics of Large Numbers: A History of Statistical Reasoning (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

[4] Alice O’Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century U.S. History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[5] Ian Hacking, “Making Up People” in Reconstructing Individualism: Autonomy, Individuality, and the Self in Western Thought, ed. Thomas C. Heller, Morton Sosna, and David E. Wellbery (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986); Ian Hacking, “Biopower and the Avalanche of Printed Numbers,” Humanities in Society 5 (1982): 279-95.

[6] See Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star, Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

[7] Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger, eds., Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), vii.

[8] Sarah E. Igo, The Averaged American: Citizens, Surveys and the Making of a Mass Public (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

[9] Felix Stalder, “Opinion: Privacy is Not the Antidote to Surveillance,” Surveillance & Society 1:1 (2002), 120.

[10] See www.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/en/research/projects/DeptII_ChamayouGregoire-Traceability.

Background image by Gerd Arntz.