As mechanical reproductions of sound, in order to be heard, a vinyl record must be taken out of its sleeve, held in one’s hands, and placed onto a turntable before the needle can drop and sound can escape. In 2010, the Nasher Art Museum at Duke University curated one of the first art exhibits dedicated exclusively to the record. At a time when music has gone digital, The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl (on view at The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston from April 15 to September 5, 2011) incorporates artwork from the 1960s to the present by forty-one artists, who examine their subject as sound, as material, and as symbol.

“The Record exhibit pins” credit: Darren Mueller

From the museum’s lobby, Satch Hoyt’s Celestial Vessel emanates Liszt, Verdi, and tracks from the RCA World Music catalog in flowing snippets. The music echoes in the large, reverberant space until no longer intelligible as sound gives way to visual representation. Next door, Lyota Yagi’s Vinyl (Claire de Lune + Moon River) (2005–09) represents the process by which meaning is grafted onto sound through repeated listening. A video screen displays an LP made of ice rotating on a turntable while the spectator listens to Claire de Lune and Moon River play in repetition. The music literally melts away, leaving aural traces on its listener. Transferred from the record into consciousness, the listener remembers not only the recently melted music, but also a not-so-distant time when music was largely imprinted on vinyl. Through the juxtaposition of one piece from the late nineteenth-century classical canon and another from the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Yagi’s Vinyl melds the ostensible highbrow and lowbrow, as well as the sonic and visual. But like ice, records cannot remain frozen in time and must also deteriorate to be heard.

“Nam June Paik’s Listening to Music Through the Mouth” credit: Manfred Montwé

With sound thereafter relegated to smaller side rooms and headphones, visual art takes center stage in the main exhibit space. Manfred Montwé’s photograph of Nam June Paik’s Listening to Music Through the Mouth (1962) depicts the artist “listening” to a record through his mouth via a phallic-shaped object—his mouth on one end of the object, the spinning record on the other. The photograph emphasizes a desire to consume the record as a material object by not only hearing it through the ears, but also tasting its vibrations in the mouth, touching its cabinet, and experiencing it from inside the body. Acting as a resonating chamber, the body amplifies sound while “feeling” it as physical matter. This image conveys an erotic intimacy with the record as the artist leans forward, eyes closed, his mouth around the phallic object. His oral rather than aural listening subverts the intimacy of private headphones.

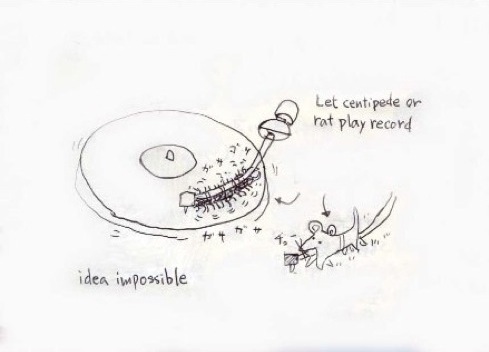

“Taiyo Kimura’s Struggling with Records” credit: Taiyo Kimura

Fifty years after Paik, Taiyo Kimura’s Struggling with Records (2008-10) similarly wrestles with the record as a material object. Kimura’s sketches show the record interacting with living things—the human body, animals, and flowers. Like Paik’s photograph, sexual sketches emphasize the forcefulness of bodily interaction with the record. In one, a couple embraces, their lips fitted through a hole in record jackets. In another, a male body with a record needle face lays atop a female body with a record face, the phallic male needle resting on the flat female record. Kimura’s work questions the continuing physical use of records. Originally used to record and disseminate sound, in this exhibit, records now serve as raw material for visual art and human interactions.

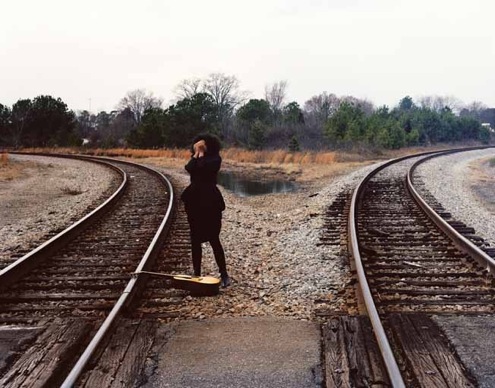

“(Place) as a time as memory as sound (place) again” credit: Xaviera Simmons

In (Place) as a time as memory as sound (place) again (2010), Xaviera Simmons offers images of North Carolina’s open spaces, old technologies, and disintegrating buildings. Simmons sent photographs to different musicians who made musical works inspired by the images. Pressed to vinyl and entitled Thundersnow Road, the recordings serve as their visual muses’ soundtrack. Available only with the purchase of an exhibit catalog at the museum, Thundersnow Road circulates outside the gallery space, functioning similarly to other records, but only to a degree. The music remains inaccessible to most and, unlike many of the exhibit’s images, trapped within the frame of the museum. For Simmons’ record to maintain its record-as-art object status, it cannot circulate freely as a consumer recording.

“Satch Hoyt’s Celestial Vessel” credit: Peter Paul Geoffrion

The Record’s eclecticism allows it to engage with visitors through different senses, the vinyl record becoming intimately tied to memory-formation and story telling. Although the exhibit effectively makes an argument for the integration of sonic and material culture, sound remains strangely remote. There are ways to exhibit sound without settling for the cacophony frequently encountered in the Nasher, but it seems that the aural component was not in fact of predominant interest for the curators of The Record exhibit. Records were, and still are to an extent, objects in motion, circling on our turntables at home and changing hands across the world in a market of sonic consumption. Now viewed and used as a nostalgic symbol of a time past, the punctured circular image of the record has become iconic in its own right. As records still sit, spin, and deteriorate over time they become meaningful beyond their sounds.

[images: Darren Mueller, Manfred Montwé, Taiyo Kimura, Xaviera Simmons, Peter Paul Geoffrion]